This article is part of a larger series on Deal Closing. Click here to access all our modules.

💡 A Term sheet is a document that lays out the basic commercials of the proposed investment.

Broadly, the contents of a term sheet can be broken down into:

Now, this is how most blogs about Termsheets begin however, they don’t do justice to completely understand what to do once someone hands a termsheet to you. We want to break down every clause in a document we typically share with founders. You can click here to access our sample term sheet, though we will bring it along with us every step of the way! With that in mind, here is how we would like to structure this conversation:

Investors usually give out the term sheet with an expiry date because they don’t want founders trying to get a better offer from another investor. Once you know which offer to accept, it’s best to sign it promptly.

Signing a term sheet is the first definitive step of a fundraise.

Having said that, it’s important that you take your time to understand the different terms, negotiate them with your lead investor as you see fit, and align on terms. Once everything is agreed upon, your lead investor will send out the final term sheet.

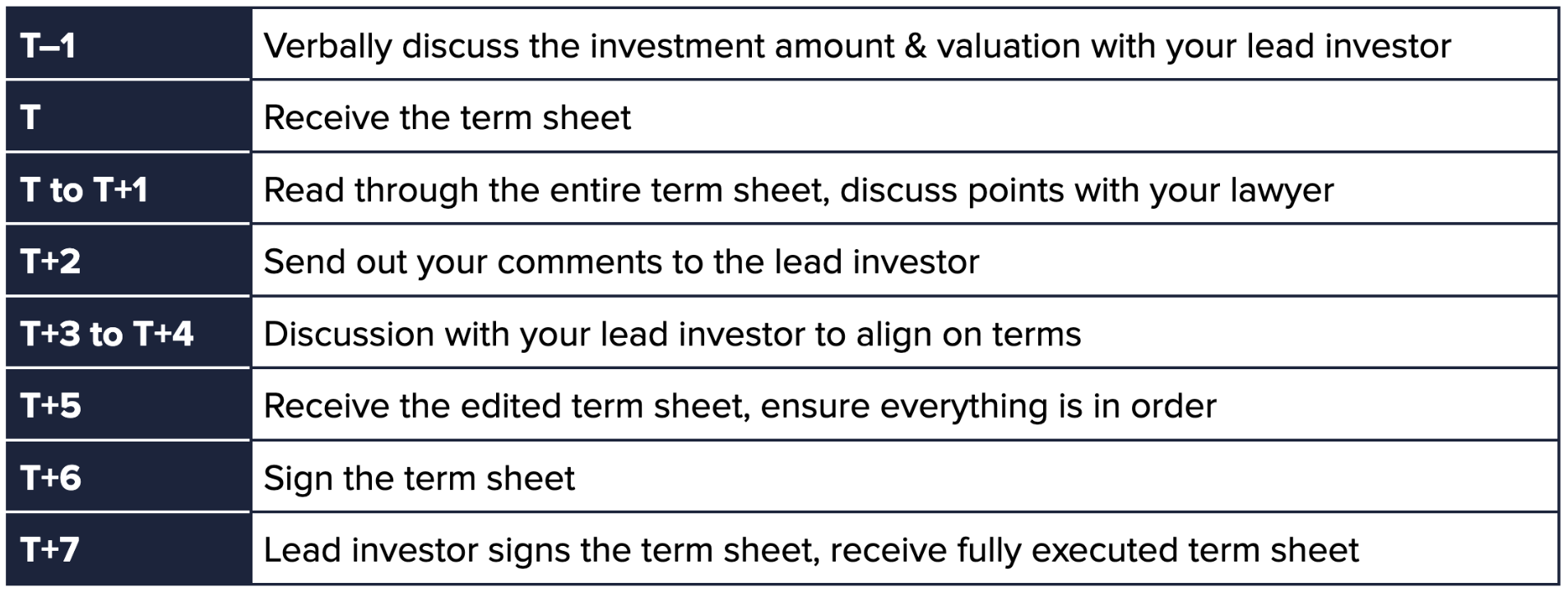

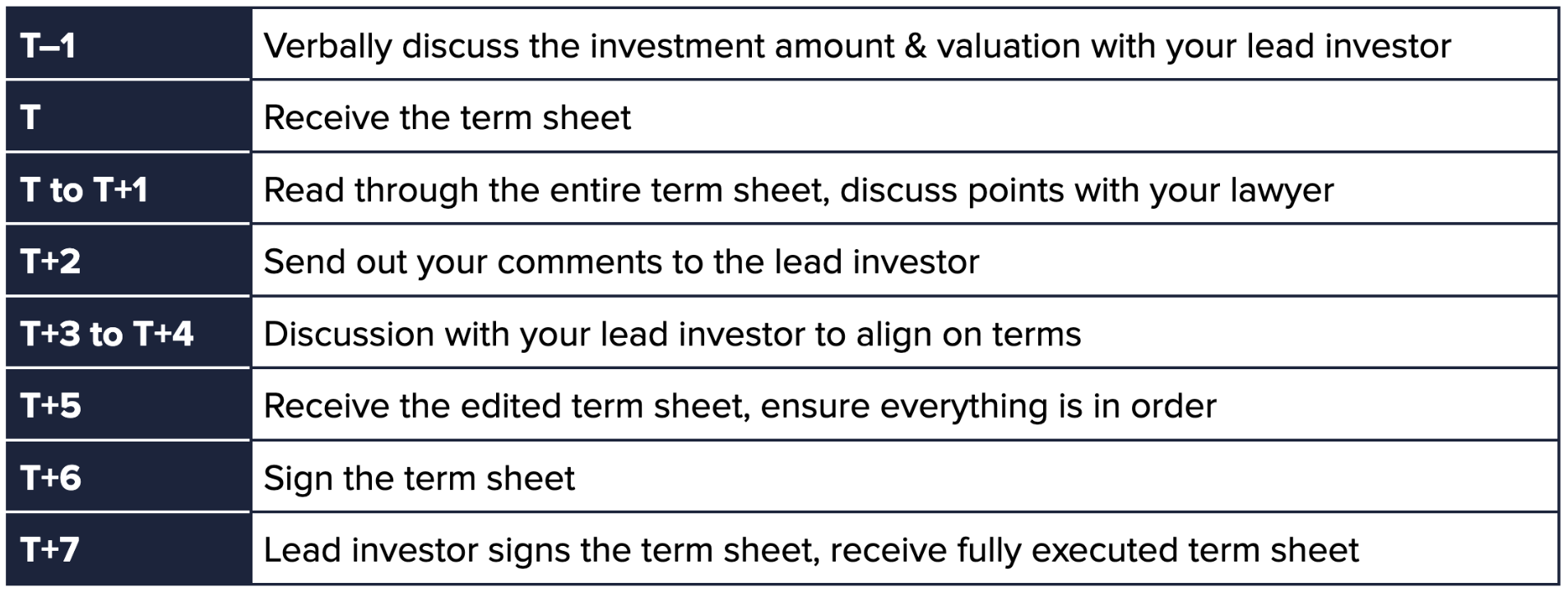

Here’s an indicative timeline of the different steps:

‘T’ being the day you get the term sheet:

After signing the term sheet, you have the detailed transaction documents, due diligence, regulatory filings, structuring the round construct, and other ad-hoc tasks.

My point being – don’t take more time than is necessary because closing anyway takes time. Try to ensure a prompt turnaround time for each step (not just for term sheet but closing in general).

A term sheet is an offer where the investor (usually the largest in the round) lists the different terms that you (the founders) and the company have to agree to.

As you would have observed in the sample term sheet, the terms are not detailed out. It only describes the essence or fundamental understanding of different terms from a business perspective (not a legal one).

The details of the different terms, the mechanism of how they will be followed, the ramifications of dishonoring the agreement – will all be covered in the transaction documents, primarily the Shareholders Agreement (SHA). This is a step after the term sheet.

A term sheet is not technically a legally binding document. However, it carries a lot of weight in that it represents the fundamental agreement between the parties.

🚨 You cannot agree to one thing in the term sheet and ask for another while negotiating SHA. 🚨

Hence, it’s important to understand everything in the term sheet, discuss clearly with your investor where you propose changes to the terms, and sign only if you fully accept what’s written in there. Of course, you might not have everything you want, but our goal is to give you a framework to make the best trade-offs.

First, let’s just zoom out a little bit and understand the different stakeholders and their commercial interests..

Now, we shall pick up each of the important terms, understand them in sufficient detail, including the perspectives of founders and investors, and their implications on the business, think about how to negotiate and try to arrive at what is usually fair.

To ensure it’s practical, we’ll pick up extracts from the sample term sheet as the basis.

There are three things here – investment amount, valuation, and type of shares.

There is little doubt that valuation is arguably the most important aspect of an offer. Remember, the term sheet timeline suggested to have a verbal conversation with your lead investor about the amount and valuation. The purpose of that is to align beforehand on the most crucial aspect.

💬 The best investors will try to have this conversation with you and try to work to what’s fair.

For a company that has little operating history, valuation is whatever the founder and investor agree it to be. Hence, it’s of little use to discuss the valuation directly. Let’s take an example.

Suppose the lead investor offers to invest $500k in a total round of $600k ($100k for other smaller investors) and offers a post-money valuation of $3mn. Now, as a founder you can directly say that I want a valuation of $4mn. But to be honest, there’s no direct rationale for arriving at either $3mn or $4mn.

💰 The valuation is a derivative of how much capital the company needs and how much ownership the investor wants or the founders are willing to dilute.

Hence, a better way to make a counter-offer is to approach it from that perspective:

Look, $600k at $3mn results in a dilution of 20% which is a bit more than what we’re comfortable with. We don’t want to go over 16% at this stage and our capital requirement is around $550k. So, we believe that we can either do $550-570k at $3.6mn post-money or raise a little less like $520-530k at around $3.4mn.

Deciding the valuation is still fully subjective but structuring it this way helps to make the conversation more rational. The investment amount comes from the use of funds that you’ll have over the next 18-24 months and dilution gives the investor a counter-perspective to think about their intended ownership.

Now, the esoteric question of starting low or high depending on what number you want to end up. Everyone tries to do it and everyone knows so not sure how effective it really is. It’s important to be absolutely clear about what you aren’t willing to budge on. Then, based on your perception of the investor, you can either go in directly with that or try to start with a different number so you eventually settle around what you originally wanted.

When the lead investor gives you a term sheet, they could leave room for other investors or just give you their offer and then it’s up to you if you want to bring in others. This is another reason why you should have a verbal discussion around the round construct with your lead investor on how much space you want to reserve for angels or other smaller funds. It helps in contextualizing the total dilution of the round and a reasonable valuation.

Investors invariably invest in a different class of shares i.e. preference shares because investors want certain rights that founders will not have and hence, holding a different class of shares makes it easier to link the rights to the class of shares held. However, since preference shares generally do not carry voting rights, the investors explicitly call out they’d still have voting rights proportionate to their holding in the company. These terms around CCPS are fairly standard.

Now, let’s discuss the different rights that the lead investor shall ask for. Instead of going in the same sequence as in the term sheet, we’ll try to discuss the points in a sequence such that it makes intuitive sense to understand them (a lot of these are interconnected or dependent on other terms).

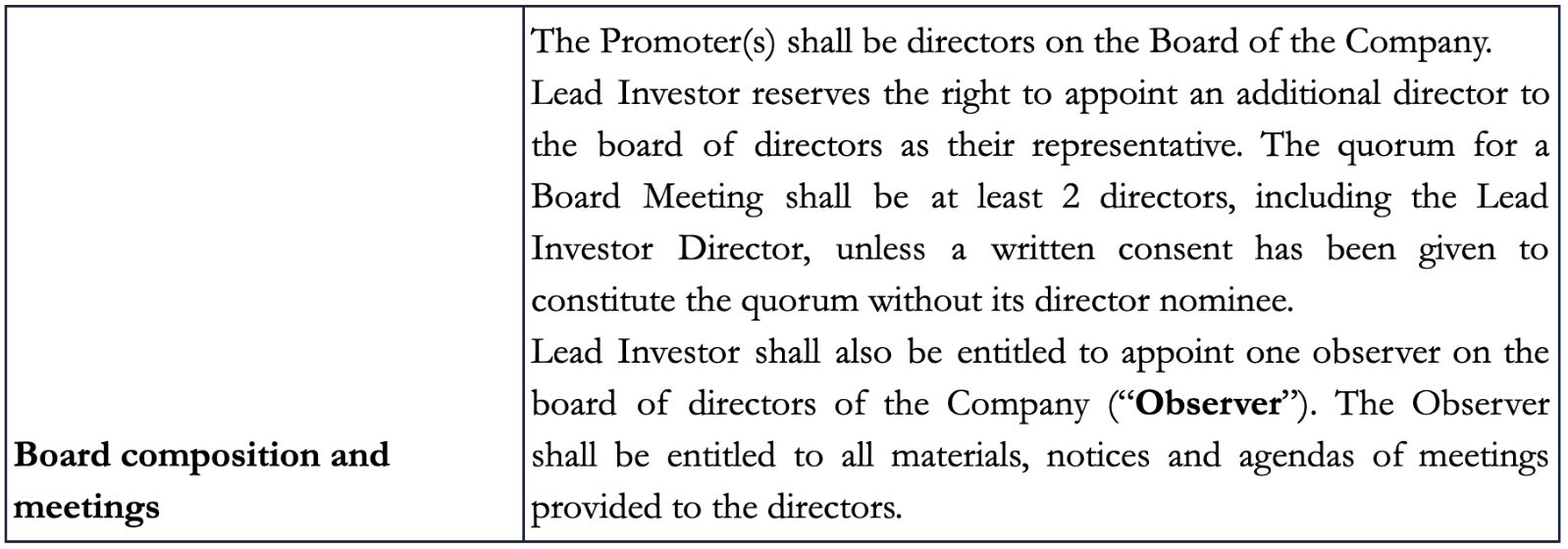

The board of directors is the governing body of a company and hence, anyone who is investing a sufficiently large amount of money will want to have a representation to have a say in important matters to preserve their interests. However, practically, at an early stage, there is little difference between the founders and the company and the board of directors. The founders are the company and control the board of directors.

The investor director seat usually comes into play as the company starts to grow and assumes a more formal organizational structure.

It’s likely that your lead investor in the future rounds will also demand a board seat and with each round of financing, the possible size of the board increases. This also means that the founders might have less control over the board as the company grows. So, it’s important to set thresholds for which an investor can have a board seat and to have strong relationships with your earlier investors who can support you as part of the board.

Investor director is non-executive which means that they do not take part in any operations or can make any decisions. However, they might reserve votes on extremely important matters, over which the lead investor will anyway require you to take their approval. On the positive side, a good investor can actually help you with good corporate governance practices.

At an early stage, 1 director seat is usually fair for the lead investor. They ask for an observer seat more from the perspective of preserving some say even in the future when they might have a much lower shareholding. It might be good to have a chat with them about when they intend to actually appoint someone on the board just so you know.

To be honest, this is the most important part of the entire transaction. Reserved matters is a list of business-related decisions where the founders/company will need to take prior approval from the lead investor. At the term sheet stage, the intent is to agree that the founders will need to ask the lead investor before taking certain decisions.

Since the exact list is not usually discussed at the term sheet stage, each item on this list is up for discussion during the SHA stage.

To still give you an idea, this includes things such as raising your next round, availing debt over a certain limit, business contracts over a certain limit, related party transactions, creating subsidiaries or entering into joint ventures, hiring or firing people above a certain pay scale.

Most of these are critical business decisions that would result in using a substantial amount of the capital that the investors have provided and hence, they’d want to protect against any scope of misappropriation. Honestly, most investors have a standard list of reserved matters and they wouldn’t be willing to remove any of them. However, the scope of threshold for these points can definitely be negotiated.

To make things easier for you, we’ll provide a sample list of these reserved matters when we discuss the SHA part of the closing process.

This one is really important because it sets the time horizon for which the investors intend to align their interests with those of the promoters. There are 3 things to unpack here – the time period itself, the exit mechanisms, and the Drag right. So, let’s take them one by one.

Most venture funds have a defined life within which they raise money from LPs (limited partners are the people who give money to VCs to invest), invest into companies, make their return i.e. get money back, and then distribute it back to LPs. The total time horizon is usually 7 or 8 years and can be extended to a maximum of 10 years. Hence, investors keep it at 5 years.

The logic here is that 5 years is a sufficient time period to build a business to a scale where investors can get an exit and hence, make a return. Further, the company gets 1 more year after 5 years to facilitate an exit (because operationally it takes time to find a mechanism and to conclude any transaction). It also provides flexibility because when the company raises another round, the exit period will be reset. So, if the next round happens 1 year later and the exit period is reset to 5 years, it becomes 6 years for the first investor.

As a founder, you shouldn’t agree to anything less than 5 years, at the pre-seed or seed stage. Certain investors might also be okay with a 6 year period. But please understand, that whatever the exit period is, investors will usually set a similar time horizon for your share vesting & lock-in (discussed later).

Now, if you read it carefully, the exit clause is worded as if it’s an obligation on the founders to provide an exit (and hence, a return) to the investors. Practically, it is not an obligation, it’s just an imperative requirement in good faith because investors understand that getting an exit depends a lot on external market factors, which might be outside the control of investors. Further, founders are not personally liable to provide an exit to investors.

The different methods of exit i.e. IPO, third party sale, strategic sale, buyback are all methods each of which will have their own process which will be detailed out in the SHA. These are the usual methods by which an investor can get an exit and hence, are listed. It might be worth going through the mechanics of each mode during the SHA stage.

Finally, let’s understand the Drag right, which might sound a little aggressive on the founders. Now, investors rely on the founders to provide an exit for the 5 years + 1 year period. However, they still want an exit in case the founders fail to do so. Practically, this would mean that the company hasn’t been able to raise another round (which gives investors comfort around the future of the business and provides an opportunity to exit) which means the business isn’t doing too well. However, they still want to get an exit because they want whatever money they can get.

In such a scenario, after the 5+1 year period, the lead investor can force all other shareholders (including founders and other investors, if any) to sell their shares, if they find a buyer.

Because, if it comes to the point where the lead has to force a sale, it means the business is not doing well and it’s more to salvage some part of the original investment than a successful exit. In such a scenario, the company, the founders or lead investors are on the backfoot vs whoever the buyer will be. Hence, the buyer will determine the terms of the transaction and might want to buy the entire company instead of a minority or even a majority stake. At such a stage, investors don’t want any restriction on their ability to facilitate an exit.

It may be but in all probability, if you’ve spent 5 years building something and it still hasn’t paid off, it might not be such a bad idea to try something else with a fresh start. In fact, in most cases, you’re more likely to shut the company down in 3 or 4 years because you run out of funds, or try for a friendly acquisition, before it really comes to the lead investor exercising the drag right, which is like a last resort.

There’s also a provision of accelerated exit in case of material breach , which is a really serious violation of the SHA. The exact scope of material breach is defined in the SHA and can be negotiated. In principle, it means you did something really unfair and unjust which seriously harms the company’s future and investors’ ability to make returns. In case the lead investor triggers material breach and founders do not rectify it, then the investors can force the founders to provide an immediate exit. In such a fire sale, it’s quite likely that any transaction will occur at a severely discounted price, which means investors will practically sell at a loss.